Prof. Dr. Markus Meier

Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW)

E-Mail: markus.meier@io-warnemuende.de

Forced and unforced climate variability#

Natural climate variability:

The climate of the Earth has always been varying over time, for different reasons. There can be forced and unforced variability of the climate.

Forced variability: Volcanic eruptions, Changes in atmospheric aerosols and greenhouse gases, Solar variability (sunspot activity, orbital parameters), Tectonic changes.

Unforced variability: Internal variability generated by the non-linear dynamics of the climate system. The climate system is a combined system of noise and system of memory, and even an unforced system inhibits low frequency internal variability due to noise and memory.

Anthropogenic impact on climate:

Forced climate variability due to human-made emissions of greenhouse gases and aerosols

Climate data: Measurements and proxy data#

Thermometer measurements#

Clear trend of increasing global surface temperature since preindustrial (~1850) times, as shown in Fig. 1 and 2. There were barely any thermometer measurements before the 20th century and even at the beginning and middle of the century the coverage was low.

A possible analysis of this temperature time series is to compute linear trends for the last 25, 50, … years. This is done in Fig. 2. But be careful, the comparison of trends of different time periods can be falsified due to the internal variability of the system.

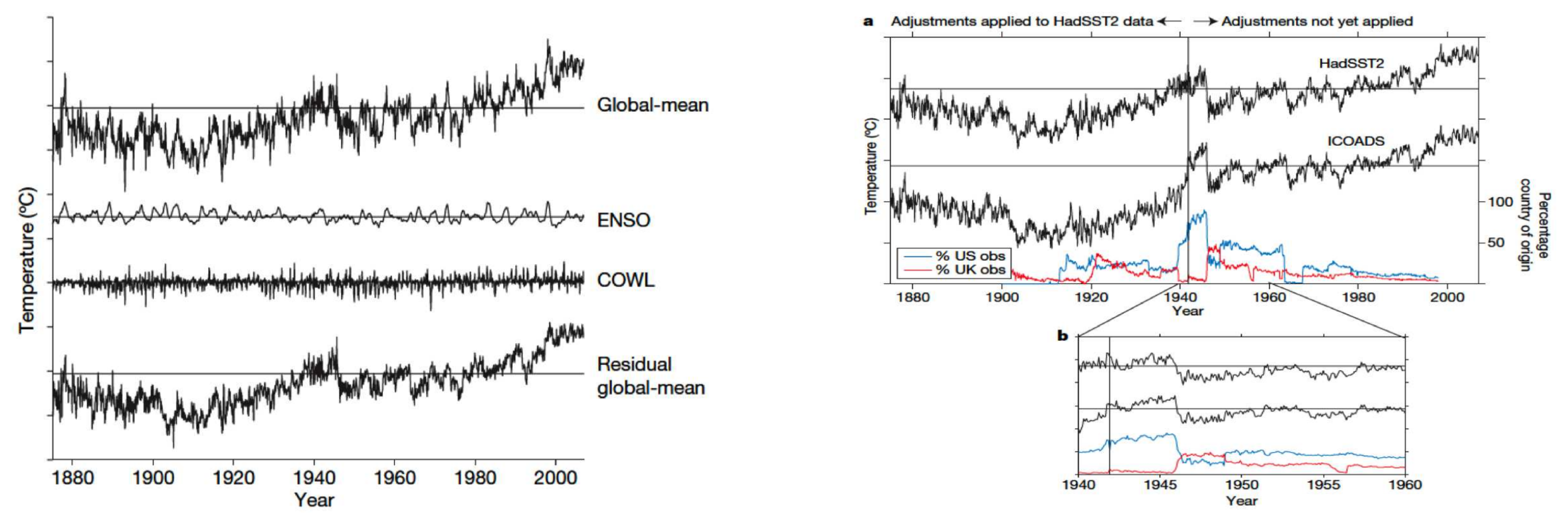

Regional temperature measurements were unequally distributed around the globe, with a better coverage on the Northern Hemisphere and gaps in the South (see Fig. 3). Also it has been very difficult to gather in-situ measurements over the ocean. Surely this had an influence on calculations of the global mean temperature. Going back in time the amount and quality of measurements decrases drastically (see Fig. 4). Geopolitical events such as wars influenced the data coverage (see Fig. 5). As a result of these factors all regional temperature variability based on thermometer measurements has to be regarded as uncertain before the introduction of sufficient measurements via satellites roughly in the 1980s.

During World War II most of the ocean measurements were done by warships. Fig. 5 shows how a drop in the global temperature time series is measured at the end of the war. This drop is very likely related to the fact that the UK ships measured in different regions of the Earth (e.g. Atlantic Ocean) than the US ships (e.g. Pacific Ocean). Disentangling the real signal from noise poses a big challenge.

Courtesy: D. Dommenget

Climate proxies#

Climate proxies are a very important subject in paleo climate science. They carry information about the climate during past times where no measurements are available. However the interpretation of these proxies is really difficult. The thickness of tree rings for example is not only dependend on the summer temperature, but also on other factors that have nothing to do with temperature, such as rainfall, extreme weather events, insects, etc.. Consequently climate proxies deliver nothing more than estimates of past climate. The estimates however are still very important, so let’s go through the most common proxies!

Tree rings are used as a proxy for summer temperature. They allow a look back in time of several hundret years, as some trees can get very old, and some old dead trees have been preserved very well.

Ice cores carry information of the last several 100 kyrs. The Antarctic ice sheet is up to 4km thick and a million years old at some places. The ratio of the oxygen isotope \(\delta\)O18 in the ice depends on the surrounding oceans and local atmospheric temperature during the time the ice sheet developed. Additionally ice cores carry small air bubbles that have preserved the chemical atmospheric composition of the past.

On top of that, ice sheets interestingly keep their temperature from the time they formed over many thousand years. Thus simple temperature measurements of ice boreholes are another great proxy.

Corals are a SST proxy in shallow waters (<5m) for many thousand years, as dead some corals have been preserved very well.

Sediments at the bottom of water bodies contain several climate indicators. They track fossils which allow insight into past climate (temperature, atmospheric composition, …) as different species thrive under different marine and atmospheric conditions. Information can be tracked back for several million years.

Climate proxies are unequally distributed around the Earth, see Fig. 10. Tree rings are predominantly taken from Europe and Northern America. Corals can only be extracted from the ocean. Ice cores are almost exclusively extracted in the Arctic and Antarctic, with some exceptions in den Andes and the Kilimanjaro.

Climate history#

The last 2.000 years#

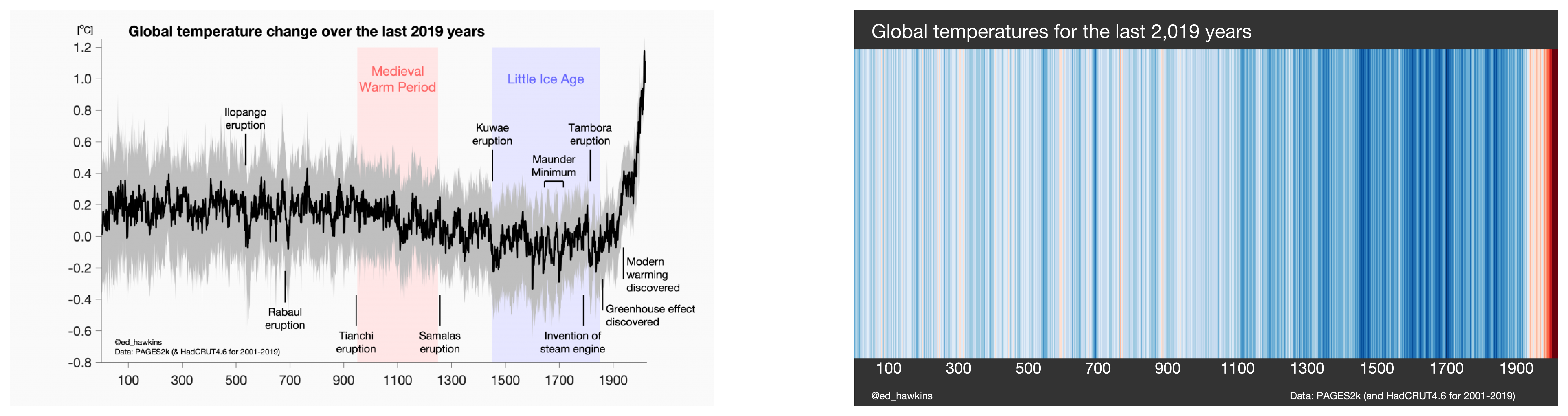

The climate of the past 2000 years has been relatively stable. Fluctuations were mainly due to internal variability with some impact of sun spot and volcanic activities, see Fig. 11.

The two most singificant climate periods over the last 2 kyrs were the Medieval Warm Period (MWP) and the Little Ice Age (LIA). Recent findings of the PAGES2K Consortium (2019) based on proxy data suggest that both periods were distinct on a regional rather than a global scale (see how the global temperature did not increase during the MWP in Fig. 12, left).

Volcanic eruptions have a strong impact on the climate system. The aerosols absorb a part of the solar radiation in the atmosphere, leading to a cooling of the Earth’s surface as it is exposed to less radiation to absorb. This is the leading hypothesis for the cause of the LIA. The atmospheric parts to which the aerosols rise quickly heat up due to the increase in absorbed radiation. Fig. 13 for example shows the temperature profile of the lower Stratosphere between 1958-2007 which is strongly influenced by volcanic eruptions.

Climate models calculate past climate differently and their temperature reconstructions vary from model to model with large uncertainties. But all of them agree on a strong temperature increase since industrial times, as shown in Fig. 14 (b).

Recent reconstruction of European summer temperatures since Roman times done by Luterbacher et. al. (2016) shown in Fig. 15.

The last 10.000 years (Holocene)#

State of the art reconstruction by Marcott et. al. (2013) based on 73 globally distributed records. There has been a temperature maximum around 6-8ky ago, called Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO), depicted in Fig. 16.

Reconstructions can result in quite different temperature trends. Fig. 17 compares different singular proxy reconstructions.

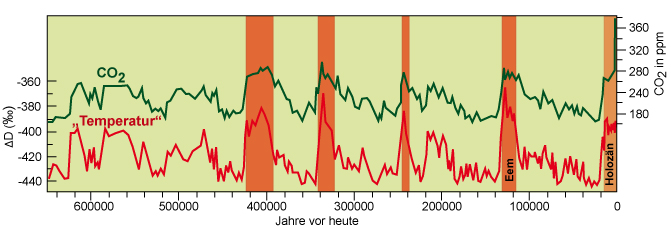

The last 500.000 years#

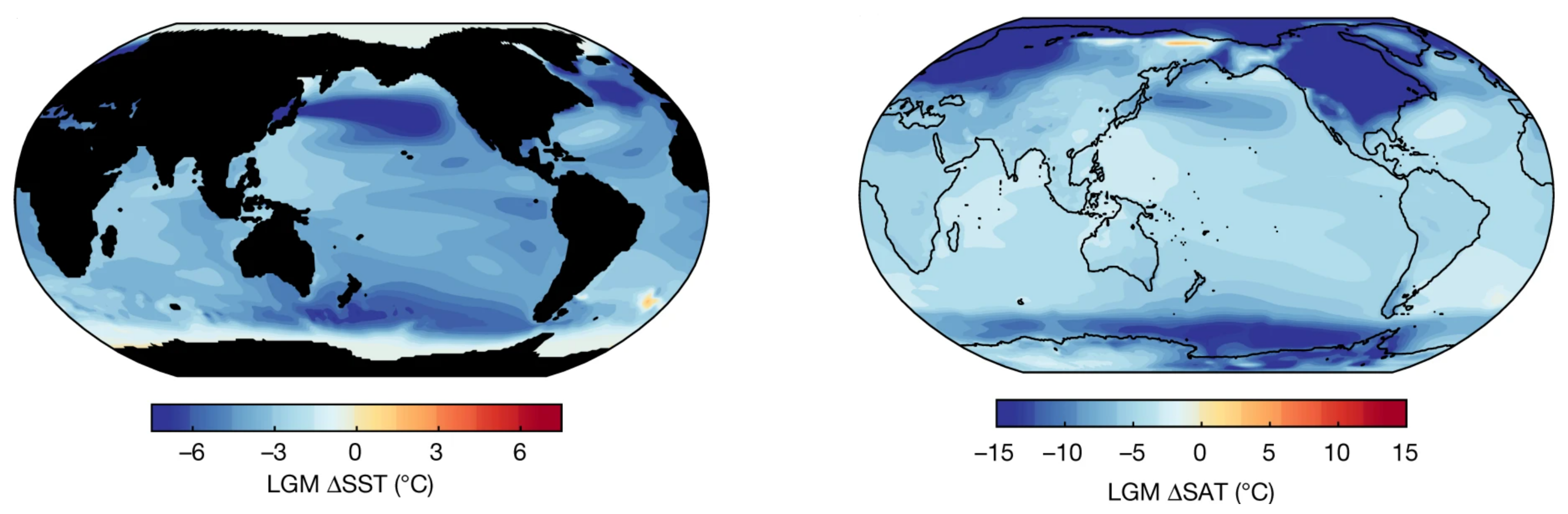

The last 500 kyrs of climate variability were dominated by Ice Ages - characterized by long interglacial periods with short interglacials of global extent. The global mean temperature differed about 3K between the two states, and even more in the polar regions. Some interglacial periods were even 1-2K warmer than today.

Best method to gather information about these times is the analysis of ice cores. The Vostok ice core drilling site (see Fig. 18) in Antarctica has the thickest ice sheet, no drift or snow and thus the oldest ice on Earth. Fig. 19 shows temperature variation estimates over the past 450 kyrs based on \(\delta\)O18 from Antarctic ice cores, including the Vostok station. It also shows approximated ice volume, which goes hand in hand with the temperature variations.

Temperature changes were rather abrupt during the last 100 kyrs. Fig. 20 shows the Greenland temperature during that period based on ice core estimates.

Deniers of human made climate change argue that climate has always been changing. And they are right, the global climate is constantly changing, but currently it does so on an unpreceeded scale. Fig. 21 illustrates how truly different present times are compared to temperature changes between glacials and interglacials.

The behavior of the climate system during the Ice Ages is truly remarkable, so let’s look at the causality behind it. It is assumed that there are two main drivers for the Ice Age cycles.

Internal natural and external climate variability, including some important feedbacks.

Ice-albedo: Ice has a significantly higher albedo (reflectivity) the the ocean. Thus is reflects more of the incoming solar radiation than the ocean, decreasing the net incoming radiation and effectively leading to a stronger cooling.

Water vapor: A colder climate causes more atmospheric water vapor to freeze reducing cloud cover. A decrease in water vapor, the strongest greenhouse gas, results in further temperature decrease.

Altitude cooling: Glaciers grew up to 4.000m high. In these heights the air pressure is substantially lower which causes water to freeze at higher temperatures above 0°C (remember phase diagram of water) additionally increasing ice volume.

Atmospheric circulation: Large glaciers (such as Greenland) have a distinct impact on the atmospheric circulation.

Land vegetation: Ice cover and colder temperatures force a change in vegetation allowing less trees to grow, which could have taken up CO\(_2\).

Oceanic CO\(_2\) uptake: Colder oceans can take up more CO\(_2\), which reduces the atmospheric greenhouse gas concentration causing further cooling.

During the Last Glacial Maximum Earth’s surface possessed a higher albedo and less atmospheric CO\(_2\), CH\(_4\) and N\(_2\)O (all greenhouse gases) resulting in a radiation difference of 6.5W/m\(^2\) compared to today (see Fig. 25). Assuming that it was about 5K colder we can deviate a climate sensitivity of about 0.77 K per W/m\(^2\).

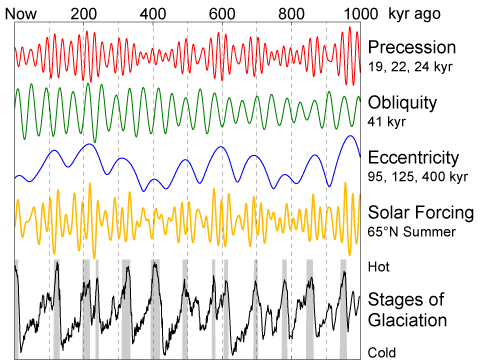

The dominant driver of the Ice Ages were variations of the Earth’s orbit called Milankovitch cycles. They describe the global distribution of solar radiation between latitudes and seasons, caused by variations of Earth’s orbit due to the gravitational pull of other planets and the moon. It is important to note, that the total solar constant (\(S_0 = 1368 W/m^2\)) changes less than \(1W/m^2\) over 100 kyrs whereas regional and seasonal changes can add up to \(50W/m^2\) over 10 kyrs.

The orbital variations consist of the following three elements:

Obliquity: The tilt of the Eart’s axis towards its orbit oscillates between 22.16°-24.5° with a period of about 41 kyrs.

Excentricity: The shape of the Earth’s orbit varies from more to less elliptical on periods of 95, 125 and 400 kyrs.

Precession: The Earth’s axis rotates perpendicular to the Earth’s solar orbit with frequencies around 20 kyrs. The Precession depends on Obliquity and Excentricity and has no effect withour either.

The combination of obliquity, excentricity and precession modifiy the Earth’s orbit and create periods where glaciation is more or less likely, see Fig. 28.

They are still questions regarding the Ice Ages which have not been answered by scientists so far.

Why is there a shift between orbital forcing and temperature that also changes in time? (Fig. 29)

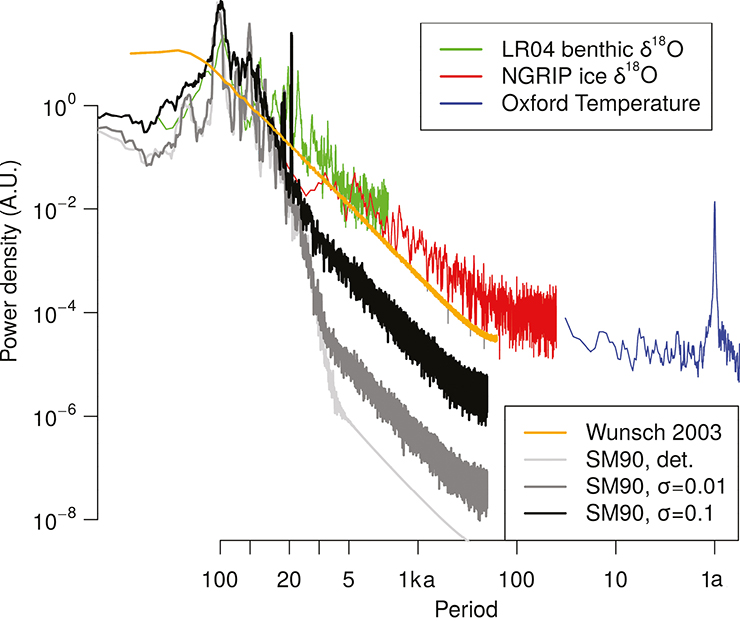

Why is the 100ky period so strong and other frequencies are not? (Fig. 30)

Why does the temperature spectum look like red noise on such a large time scale?

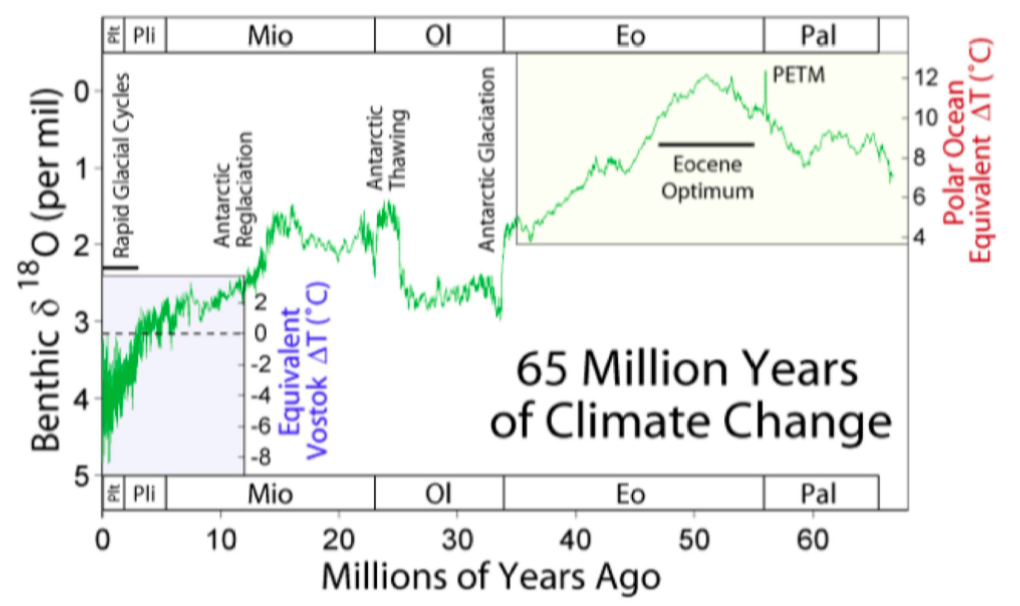

The last 65 million years (Cenozoic)#

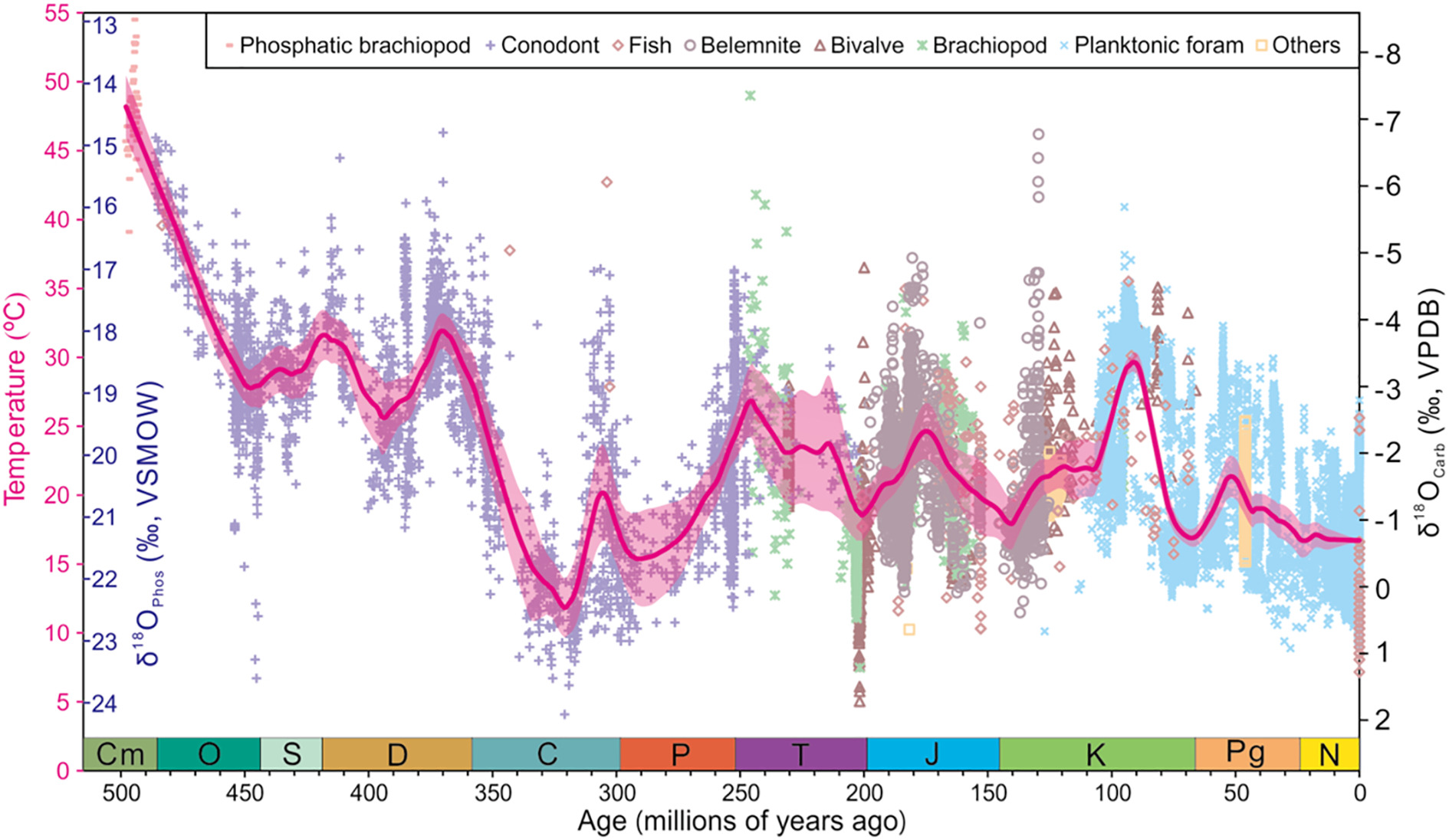

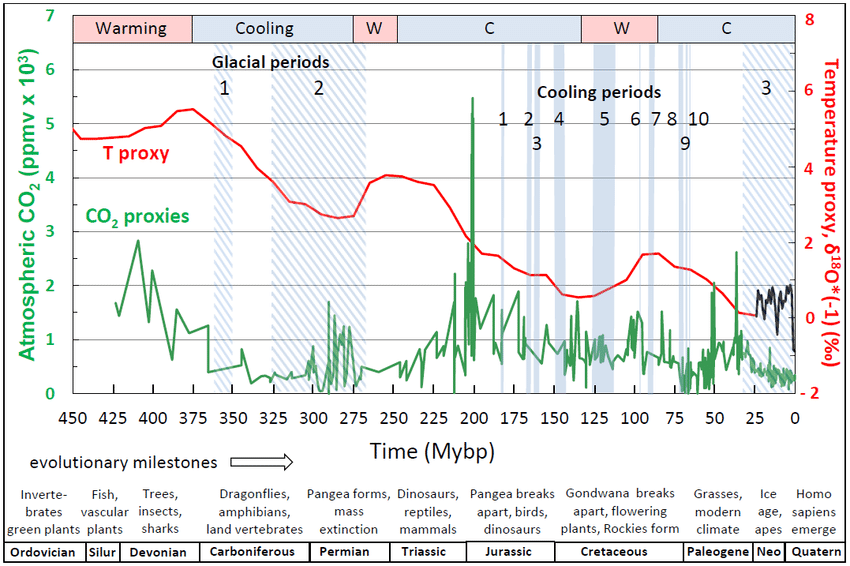

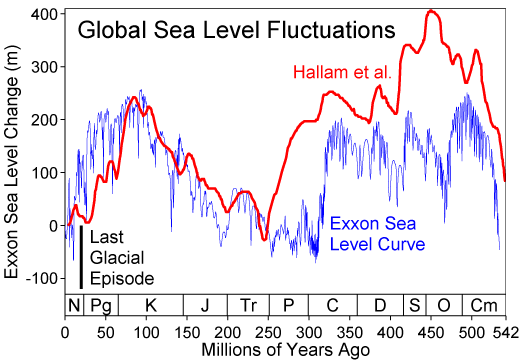

The last 500 million years (Phanerozoic)#

Anthropogenic impact on climate#

This section is based on the summary for policymakers of the 6th Assessment Report of the IPCC from 2023. View here!

IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Human influence has warmed the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2000 year, probably even for way longer. Remember Fig. 21, the sketch of the different rates of changes for human-made and natural climate change - the trend via anthropogenic forcing is multiple times steeper.

Observed warming is driven by emissions from human activities, with greenhouse gas warming partly masked by aerosol cooling. The most dominant factor forcing global warming is the emission of carbon dioxide, followed by methane. The emission of aerosols, predominantly sulfur dioxide, yield cooling of the Earth - but these aerosols are still really bad for the environment.

Climate change is already affecting every inhabited region across the globe, with human influence contributing to many observed changes in weather and climate extremes. Hot extremes are happening increasingly often in almost every region across the world with high confidence of human contribution. Many regions also experience an increase in heavy precipitation and agricultural and ecological drought. The human contribution to the increases is not as certain as to the hot extremes.

Five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) of the IPCC model the future emission of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and sulphur dioxide until 2100. Future emissions cause future additional warming, with total warming dominated by past and future CO\(_2\) emissions for every regarded SSP.

With every increment of global warming, changes get larger in regional mean temperature, precipitation and soil moisture.

Not only do the regional differences in temperature, precipitation and droughts increase. The report also projects changes in extremes to be larger in frequency and intensity with every additional increment of global warming.

If atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations increase the land and ocean carbon sinks will take up higher amounts of it, but not proportionally as much. For higher cumulative CO\(_2\) emissions the percentage of emissions that are taken up by land and ocean carbon sinks decreases.

The increase in global temperature is not the only consequence of human activities. All major climate system components are affected, amongst other things Arctic sea ice is melting, the ocean experiences acidification and the sea level rises. Some responses take decades and others centuries.

Climatic impact-drivers (CIDs) are physical climate system conditions (e.g., means, events, extremes) that affect an element of society or ecosystems. Depending on system tolerance, CIDs and their changes can be detrimental, beneficial, neutral, or a mixture of each across interacting system elements and regions. The AR6 projects multiple CIDs to change in all regions of the world.

Table of figures#

Figure 1: Figure 6.129 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 2: Hamburger Bildungsserver, Klima im 20. Jahrhundert: Arbeitsblatt. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Klima_im_20._Jahrhundert:_Arbeitsblatt, access on 05.04.2024

Figure 3: Figure 6.130 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 4: Figure 6.131 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 5: Figure 6.132 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 6: Figure 6.133 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 7: Figure 6.134 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 8: Figure 6.135 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 9: Figure 6.137 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 10: Figure 6.138 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 11: Figure 1 in Hamburger Bildugsserver, Externe Klimaschwankungen. https://bildungsserver.hamburg.de/themenschwerpunkte/klimawandel-und-klimafolgen/klimawandel/externe-schwankungen-252834, modified to English.

Figure 12: Hawkins, E. (2020). 2019 years. https://web.archive.org/web/20200202220240/https://www.climate-lab-book.ac.uk/2020/2019-years/

Figure 13: Figure 2 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Nachweis einer anthropogenen Klimaänderung. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Nachweis_einer_anthropogenen_Klimaänderung

Figure 14: Figure 10 in Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007 Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Figure 15: Figure 3 in Luterbacher et. al. (2016). European summer temperatures since Roman times. Environmental Research Letters. 11. 10.1088/1748-9326/11/2/024001.

Figure 16: Scott, M. (2014). What’s the hottest Earth has been “lately”?. NOAA Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-qa/what’s-hottest-earth-has-been-“lately”

Figure 17: Figure 1 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Holozän. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Holozän, modified to English.

Figure 18: Figure 6.143 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 19: Figure 6.144 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 20: Figure 6.142 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 21: Figure 6.145 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 22: Figure 2 (a) and (b) in Tierney, J.E., Zhu, J., King, J. et al. Glacial cooling and climate sensitivity revisited. Nature 584, 569–573 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2617-x

Figure 23: Figure 4 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Die Erdneuzeit (Känozoikum). https://bildungsserver.hamburg.de/themenschwerpunkte/klimawandel-und-klimafolgen/klimawandel/das-kaenozoikum-252984

Figure 24: Figure 3 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Eiszeitalter. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Eiszeitalter

Figure 25: Figure 7 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Eiszeitalter. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Eiszeitalter

Figure 26: Modified Figure 1 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Eiszeitalter. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Eiszeitalter

Figure 27: Rohde, R. A., Milankovitch Variations. Under CC BY-SA 3.0. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milanković-Zyklen#/media/Datei:Milankovitch_Variations.png

Figure 28: Modified Figure 5 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Eiszeitalter. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Eiszeitalter

Figure 29: Figure 6.155 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 30: Figure 1 in Ditlevsen, Peter and Crucifix, Michel (2017).On the importance of centennial variability for ice ages. Past Global Changes Magazine. 25(3), p.152-153. https://doi.org/10.22498/pages.25.3.152

Figure 31: Modified Figure 2 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Eiszeitalter. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Eiszeitalter

Figure 32: Figure 6.155 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 33: Modified Figure 1 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Kohlendioxid in der Erdgeschichte. https://bildungsserver.hamburg.de/themenschwerpunkte/klimawandel-und-klimafolgen/klimawandel/treibhausgase/kohlendioxid-erdgeschichte-253406

Figure 34: Modified Figure 1 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Känozoikum. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Känozoikum

Figure 35: Modified Figure 3 in Hamburger Bildungsserver, Känozoikum. https://wiki.bildungsserver.de/klimawandel/index.php/Känozoikum

Figure 36: Figure 8 in Scotese, C. R. et. al. (2021). Phanerozoic paleotemperatures: The earth’s changing climate during the last 540 million years. ScienceDirect. 215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103503.

Figure 37: Figure 5 in Davis, William. (2017). The Relationship between Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Concentration and Global Temperature for the Last 425 Million Years. Climate. 5. 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli5040076.

Figure 38: Rohde, R. A.. Creative-Commons license. https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Phanerozoic_Sea_Level.png

Figure 39: Figure 6.163 in the lecture notes of Dietmar Dommenget: An Introduction to Climate Dynamics, https://users.monash.edu.au/~dietmard/teaching/dommenget.climate.dynamics.lecture.notes.pdf

Figure 40: Figure SPM1 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 41: Figure SPM2 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 42: Figure SPM3 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 43: Figure SPM4 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 44: Figure SPM5 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 45: Figure SPM6 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 46: Figure SPM7 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 47: Figure SPM8 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

Figure 48: Figure SPM9 in IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I

to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L.

Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K.

Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New

York, NY, USA, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001